Pendulum # 23

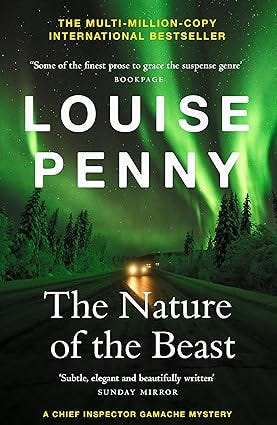

The Nature of the Beast

I was in a quandary about what to call this edition of The Pendulum. At first I called it “deontological versus consequentialist ethics” or perhaps “deontological versus consequentialist ethics in fiction.” How dry and boring is that!

In her novel, The Nature of the Beast, Penny’s most political novel, two people are murdered. Late in the novel it is suggested they may have been murdered to prevent the plans for a long-hidden weapon of mass destruction from falling into the wrong hands. Former Chief Inspector Gamache, now retired but still working the case on the sidelines, is confronted by a government spy who argues, basically, that sometimes people need to be sacrificed for the common good. That confrontation is reproduced below, as is an excerpt from Hank Rearden’s courtroom speech in Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. Both Gamache and Rearden argue against the cult of sacrifice. But first, I discuss the difference between deontological and consequentialist ethics.

Since the beginning of the month I’ve finished reading Knowledge, Value, and Reality: A Mostly Common Sense Guide to Philosophy by Michael Huemer, Freedom and Its Betrayal: Six Enemies of Human Liberty by Isaiah Berlin, and The Nature of the Beast by Louise Penny. And I read the first two chapters of The Crooked Timber of Humanity, also by Isaiah Berlin, which I had snagged at a second hand bookstore recently.

Huemer’s book is billed as an introductory book on philosophy and it is that, but it is far more than a standard introductory text you’ll find in a Philosophy 100 course. It covers a wide range of issues and takes an interesting approach to explaining issues and ideas. Huemer is an intuitonist. He explains complex ideas by taking intuitive notions and building on them to argue for more complex ideas by analogy. In the course of the book he explains several different approaches to ethics. One is deontology and another is consequentialism. These are the most common arguments in favor of libertarianism.

Consequentialism is a variant of utilitarianism. As he defines it, consequentialism is the view that “the right thing to do is always whatever produces the best consequences overall in the long run. That is: You should always make the choice such that, if you make it, the greatest amount of good will exist, out of all the choices available to you.” (page 242)

Huemer uses a popular thought experiment devised by philosopher Phillipa Foot to explain the consequentialist view, the famous Trolley Problem. You may have seen the Trolley Problem dramatized in the television series The Good Place. A trolley is barreling along towards five people tied to the track. But there is a switch that will divert the trolley to another track where it will kill only one person. Do you throw the switch? Do you sacrifice one person to save five? The consequentialist answer is yes.

Deontology, on the other hand, “is defined as the denial of consequentialism.” (page 257) This is a rather simplistic definition which defines the term in terms of what it is not. But he goes into a lengthy elaboration on the subject which clarifies to some extent without coming up with a definitive definition. In his glossary of terms at the end of the book the definition remains much the same: “The view that right action is not always the action that maximizes the good; the negation of consequentialism.” (page 320) The best elaboration he offers is in a footnote to the original definition where he explains that the literal meaning of the term is “study of duty.”

But the best understanding in my view is his explanation of absolute deontology or absolutism, “which holds that there are certain types of action that are always wrong, regardless of how much good they may produce or how much harm they may avert.” (257) Natural law theory and human rights theory are both often based on deontological considerations.

While libertarians are divided on supporting libertarianism for deontological or consequentialist reasons, deontological libertarianism is almost always absolutist. Its defining rule is the so-called non-aggression principle.

The best explanation of this principle was enunciated by Ayn Rand. She argued that the use of force can be manifested in three different ways. It can be initiated by an individual or group of individuals against another individual or group of individuals, or it can be used in self-defense, or it can be used in retaliation against those who have initiated it.

And in the deontological libertarian position, the injunction against the initiation of the use of force is described as a right to act unimpeded by others. That is it is wrong to forcibly impede people’s peaceful actions. Property rights are considered an extension of the self and thus an essential right. Rand famously said “Without property rights, no other rights are possible.”

But libertarianism so considered is just one of many variants of deontological thinking.

My understanding of libertarianism and Objectivism was and is largely deontological. It is an absolute view of right and wrong. Right and wrong are not a matter of outcomes such as the greatest happiness for the greatest number, but are determined by the very nature of one’s actions. You need just look at an action and if it violates someone’s individual rights, in other words, if it violates the injunction against initiating force, it is wrong on the face of it.

Perhaps the most powerful invocation of this principle is Ayn Rand’s assault on altruism. It should be noted that Rand distinguishes altruism from benevolence. Benevolence is voluntarily undertaken action to help others in need. Altruism she regards from the Comtean perspective. As Wikipedia describes it: “He believed that individuals had a moral obligation to renounce self-interest and live for others.” In his own words, “[The] social point of view cannot tolerate the notion of rights, for such notion rests on individualism. We are born under a load of obligations of every kind.” Catholic theologian Gabriel Moran put it this way: “The law and duty of life in altruism [for Comte] was summed up in the phrase: Live for others.”

Rand best explained this in her denunciation of sacrifice. Sacrifice, as she defined it, is not the forgoing of a current benefit for a future benefit.

“Sacrifice” does not mean the rejection of the worthless, but of the precious. “Sacrifice” does not mean the rejection of the evil for the sake of the good, but of the good for the sake of the evil. “Sacrifice” is the surrender of that which you value in favor of that which you don't. (Galt’s Speech, Atlas Shrugged)

One famous example she gives is that if a mother gave up some benefit to herself in order to feed her child, that is not a sacrifice. But if she let her own child die so that someone else’s child might live, that is a sacrifice.

She dramatized this magnificently in Atlas Shrugged at steel magnate Hank Rearden’s trial. He had been charged with violating a number of regulatory statutes designed to hamper his production. These were designed to help out his rival steel producers. He argues against this cult of sacrifice.

If it were true that men could achieve their good by means of turning some men into sacrificial animals, and I were asked to immolate myself for the sake of creatures who wanted to survive at the price of my blood, if I were asked to serve the interests of society apart from, above and against my own—I would refuse, I would reject it as the most contemptible evil, I would fight it with every power I possess, I would fight the whole of mankind, if one minute were all I could last before I were murdered, I would fight in the full confidence of the justice of my battle and of a living being’s right to exist. Let there be no misunderstanding about me. If it is now the belief of my fellow men, who call themselves the public, that their good requires victims, then I say: The public good be damned, I will have no part of it! (Atlas Shrugged, quoted on page 117 of For the New Intellectual)

This is the deontological stand. The consequences of murdering Hank Rearden be damned. The immorality of his murder is paramount and supersedes all other claims.

While some variants of the Trolley Problem are suggested by Huemer, including pushing a large man off a footbridge in front of the trolley to stop it from running over the five people, he does not include this variant: Would you, standing on the footbridge, knowing that jumping off the bridge in front of the train would stop it, jump? Would you sacrifice yourself to save five people? Would you feel a moral obligation to do so? Would you, in fact, have a moral obligation to do so? Hank Rearden adamantly says no!

Here’s another variant: Would you throw the switch to divert the trolley from killing five people to the track where only one would be killed if that one person was your own child? Would you sacrifice your own child to save five people? Would you be obligated to do so?

Such scenarios dramatized bring home the horror of sacrificing anyone for the so-called greater good.

In her novel, The Nature of the Beast, Louise Penny also dramatizes this conflict between deontological principles and consequentialism. Two murders have occurred. A professional government spy berates Chief Inspector Gamache who is trying to solve the murders, who is trying to find justice for the victims of these horrific crimes. The spy argues that these murders were necessary to prevent a weapon of mass destruction from falling into the wrong hands. (The following has been modified to avoid a spoiler.)

‘You have no idea of the things I see,’ she said, her voice hard and clipped. ‘And have seen. You have no idea what I’m trying to prevent.”

‘You accuse me of not understanding your world,’ Gamache said. ‘But you no longer understand mine. A world where it’s possible to care about the life of [the victim], and to be enraged by his death. A world where [the other victim’s] life and death matter.’

‘You’re a coward, monsieur,’ she said. ‘Not willing to accept a few deaths to save millions. You think that’s easy? Well, it’s easy when you run away, as you’ve done. But I stay. I fight on.’

‘For the greater good?’ asked Gamache.

‘Yes’

He got up, suddenly repulsed, and stood in the middle of the charming room.

‘I don’t think what you do is easy,’ he said. ‘At least, not at first. I think it’s soul-destroying. But once that happens, it gets easier. Doesn’t it?’

[She] stood up then and faced him.

‘Go to hell,’ she said quietly.

‘I will. If necessary. I expect I’ll see you there.’

My gut reaction when I read that was that I felt the same as Gamache. I was repulsed and revolted. The reaction was instantaneous and visceral. And it told me that at my core I am a deontologist. The evil of an action is in the nature of the action, not in the nature of the motive. Murder of an innocent life is murder, plain and simple.

Nevertheless, part of me has also come to the conclusion that such absolutist thinking is problematic. But it remains very appealing. Why do I think it’s problematic?

There are two remarkable essays leading off Berlin’s The Crooked Timber of Humanity. The first is a biographical odyssey called The Pursuit of the Ideal. In it Berlin explains how he came to reject idealism and embrace value-pluralism. I’ll discuss that in another essay. But for now I want to examine the second essay, The Decline of Utopian Ideas in the West. What is of particular interest here is his discussion of the essential incoherence of utopian or absolutist thinking. And its essential folly.

Ironically, Objectivism and libertarianism are ostensibly based on individualism. And they are based on an absolutist deontological argument. They are based on a utopian ideal. But Berlin argues that individualism and utopianism are necessarily at odds with each other. Are necessarily self-contradictory. It is a subtle argument which I will explain at length in the next issue of The Pendulum.

I should add that my purpose in writing The Pendulum is to reconcile these two principles, deontological ethics and consequentialist ethics, in a way that supports both positions.

To be continued!

Brief notes: In the last issue I mentioned that I was going to write the Introduction for the book and publish it here. I haven’t forgotten about that, but I got started on the Introduction and realized that the book’s outline needs a drastic overhaul. It goes off on too many tangents. So it is back to the drawing board. The ideas in the current essay above and the next one on problems with absolutist deontology are essential to my argument.

Links of Interest

Heaven, Hell, and the Multiverse — a look at the television series The Good Place and the Academy Award winning movie Everything Everywhere All at Once. I discuss them with respect to the lessons that can be learned from each. It includes a brief mention of the Trolley Problem.

The Pivotal Influence of Machiavelli on Isaiah Berlin’s Value-Pluralism — an essay I wrote on Machiavelli for a political science course I took at university. Berlin’s value-pluralism is an integral part of the ideas I am arguing for in The Pendulum. I’ll be writing a further essay on value-pluralism in the near future.

Too much analysis leads to too many contradictions. Just one.

Rand argues for property rights as being foundational. Slave owners ignored the rest and focussed on that to rationalize their actions.

I argue for “intervalism”, the assumption that change toward cooperation and fulsome communication is made one-person-at-time, in teeny-tiny steps.

In case you’re wondering - I just made that up.

I try to keep stuff simple. It’s more fun.